The future is something which everyone reaches at the rate of 60 minutes an hour, whatever he does, whoever he is.

- C. S. Lewis

Unbinding Time and Space

EDITOR’S NOTE

Time is the longest distance between two places — Tennessee Williams, The Glass Menagerie

Remember, be here now

— Ram Dass

Our perception of time and sense of place is both mysterious and variable. Mood and activity all affect where, and even who we are within a series of moments that can plod or whoosh by depending on the company. Can we ever simply and objectively exist?

The idea of embodying a purer temporal existence, summed up by the phrase 'be here now', gained prominence in the West via a book by Ram Dass (1971), a song by George Harrison (1973) and with some ironic referential nostalgia by the band Oasis in 1997. Recently, the phrase has found new life as a corporate maxim to mean turn off your phone, tune out the email notifications and fully participate in a spreadsheet exercise. At such times we often acknowledge that physical presence is as presence does despite our dreams of elsewhere.

In the world of art the transportive role of imagination and presence has been long appreciated. We expect art to hold our attention and by a variety of subtle and gross techniques surround and send us into its orbit. That art should be here to do this might be the defining factor in separating it from the latent visual world of decoration. A good decorative object is only mildly diverting and thus able to be ignored, characteristics that we expect true art to reject.

In this issue of Trebuchet we feature artists who use time and space as the mediums, methods and subjects of their work. From the temporal portraits of Jordan Baseman to the astronomical spirituality of Mark Batty and David O'Malley, we hope you enjoy the time spent with these less expected, though vivid constellations of contemporary art.

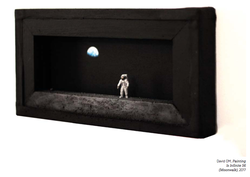

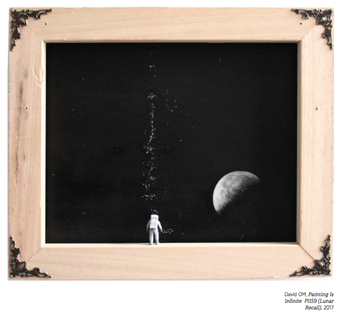

Looking at the work of painter David O'Malley, we see explorations of space as a subject, drawing on idealised perceptual space to position the functional components of his work: the viewer, the frame, scaled space, and the artwork as a discrete object.

There is of course the interplay of positive elements within each of the paintings and beside these are negating or illusory aspects which are not possible to specifically depict, which is to say that we have the drama of day (stars) and night (space) represented even if the topic is space itself. In fact this duality is absolutely necessary so that the immanent 'spaceness' of space comes across in the work. If conditions are correct this can produce a sense of cosmic mind expansion in the viewer, where a nuanced painting describes with negative space rather than explicit detail, and creates a narrative from related meanings rather than a procession of visual facts. Picking up on Derrida's appreciation of presence and différances (a fluid extension of Saussure's more static concepts of differential meaning), which to simplify for our purposes is that which is (day) and that which is borne as a concept because it cannot be, and its cousins who also aren't (night, and other things of darkness).

Saussure famously demonstrated that language (or any system of signs) works not in terms of material substances but formal differences. The sound /b/ in the word bat functions successfully not because there is anything inherently appropriate about a voiced bilabial plosive in this position but because it is different from the other phonemes that could have occurred here, such as /m/ or /s/. Its ability to participate in the creation of meaning, therefore, depends as much on what it is not as on what it is. It thus bears the trace of other possibilities and is not entirely present to itself. Presence and absence are not mutually exclusive opposites; Saussure’s differences, which underlie all meaning, are différances.

(Attridge 2019)

Day and night and Earth and Space are in such a way complementary in that they create the conceptual necessity of each other even if they have a paradoxical or contradictory relationship from our earthbound human perspective. Our feelings that day and night are intrinsically different vanish once we consider the rotation of the Earth from the Sun's perspective. Space is equally a matter of perspective as a concept of nothing between more than two points of nowhere, or just indistinctly far away.

Painted depictions of space give us something more than the high resolution images taken by NASA. Presented as a painting we are able to become part of a human interpretive relationship with the infinite nature of space. Eliciting that romantic sense of the sublime where we are driven beyond our imagination and have to rely on reason to come to terms with the beyond (such as in Kant's Mathematical Sublime). Considering the work of the two contemporary painters presented here, one realist and one more conceptual, we see how a common appreciation of space as both infinite and The Infinite can be used to very different ends. While both Batty and O'Malley are playing with the concept of perspective the axes of viewer, work and concept are nuanced, in order to look 'there' and ask questions of society, scale, self and sublime consciousness.

Through art, space and its components can be used to describe a variety of 'spaces' and even the interplay or differences between those concepts. Associations which wheel and change like constellations as we search for meaning, positions and perspective within night-bound heavenly bodies.

David OM:

Beyond the Look and the Look Beyond

"Essentially I am drawn to the power of vastness and the context of the wider picture; the compelling journey from that which is constricted within to the cusp of the infinite. An existential undertow may be detected from ruminations on the metaphysical aspects of time and space. I seek to instil a pure sense of wonder in my work that will guide the viewer to tap into the awe of the sublime and transport the individual. I am particularly fond of a David Lynch quote postulating that the restrictions of the film-making process do not apply to the field of painting and that indeed ‘painting is infinite’. "

(David OM)

The work of David O'Malley (often styled as David OM) twists the conception of viewer and viewing by using the idea of painting itself as the site of activity in his conceptual paintings. Originally educated in the north-east of England his work has been selected and recognised by a number of competitions including the John Moores Painting Prize and BP Portrait, and has exhibited internationally. Themes of metaphysics, spirituality and dispassionate existentialism are explored within a variety of cosmic subjects that have their roots in painting but are pushed beyond standard conventions of presentation. We see frames reversed and are asked to imagine the 'art' as before and beyond the painted canvas.

A key aspect of O'Malley's work is the extension of the painting into an emanating conceptual field that includes the viewer as part of its activity. Common to both his and Batty's work is a conscious awareness of how the viewer is positioned towards the depicted segment of space, as defined by the scale and frame of the painting itself. However O'Malley uses a small figurine as a proxy for the viewer and in doing so is able to increase the scale of the painting relative to that person without increasing the size of the canvas. It also signposts the action of the painting as being diffuse rather than simply on the canvas.

The pivotal importance of the Apollo photos showing the Earth has been linked to a change in how we viewed our place on the planet and in the universe, along with a corresponding change in how we viewed ecology (McCarthy 2012). Photos from the spacewalk are particularly important for global society: it was the first factual, visual story of the Earth and its inhabitants. For Batty and O'Malley, artists who work with the idea of cosmic perspective, it's a reference they understand. The planet we see is the full and perhaps final encapsulation of humanity in space, within a single frame. It is our canvas and a frame holding all we have known. The ultimate group shot, a photographic trope that older readers might remember as preceding the selfie.

How do you start looking at a work |of contemporary art? It might be that we consider the variety of levels in play and then think about what is familiar and what is not familiar, what is purposeful and what may be arbitrary, and what may be us rather than the artist. Amongst those considerations we can ask what are the boundaries defining the work and compare that to the artist’s oeuvre: is the work within a series or a standalone piece? Artists are of course aware of these processes in creating their work. It is completed when they have defined it to their satisfaction or where nothing more can be added to make the piece more immanent of its nature.

In O’Malley’s work the perception of the canvas as the standard plane of action is questioned by the reversal of the canvas and the addition of the figurine. By these actions we’re asked not to view the surface of the canvas as the limit of the work’s reality but look wider and consider how canvases are historically looked at and how those elements are played with here.

On one level you might see the main surface of the canvas as being a window out to space, the reversal of its frame being a flip side of what we think of as inside and outside. Taking a cue from this we can follow the suggestion there might be a normal viewer looking at the space canvas from the other side. What would they see? Would they see a blank canvas, the reverse of the painting of space, or would they see a window into the gallery complete with a small figure facing them?

The act of trying to work out where we are in relation to this work echoes Sartre’s description of the look in Being and Nothingness (1943). He describes a voyeur peering through a keyhole becoming aware that they too are being watched and in that realisation becoming aware of their role as an object in another’s world and therefore becoming self-conscious. In O'Malley's Painting is Infinite series this process is mirrored within itself. The transcendence described by O’Malley is the elevation of the viewer in scale as they become aware of their relationship with the Earth and the cosmos. What Sartre might describe as the subjugation of the self as object in another's gaze, O’Malley describes as the relationship between the viewer and the figure, empathetic but also transcendent.

O’Malley's flipping of scale and position can work as an ego-destroying tool of disorientation and/or a method of appreciating the infinite. His use of the figurine allows us to feel larger than the work itself and contrasts with our understanding of the vastness of space. The conceptual level of the work is compelling and fun when considering the various twists of orientation that O'Malley's paintings suggest. For instance are we a) a hidden natural viewer looking at the usual side of the canvas from a theoretical position in a wall somewhere, or b) the small figurine through which we feel the perspective and position of space, in theory infinity scaled down. Or, perhaps we are c) ourselves, giant parts of the work and part of the extended tableau of a universe. Arguably, O’Malley wants to converge all conceptions of scale in on themselves, and while the figure is a focal point it is also a red herring. The role of viewer (where we see the work), action (the figure looking into space), the physical mise en scène of the work itself and finally the inferred stage of the cosmos, is in a sense entire and perhaps infinite. Clearly the surface of the painting and the text we're asked to read is in the conceptual space, the parameters of which O'Malley reminds us are infinite.

Exploring Space and the Spatial

Space has been the metaphor for societies' outer consciousness; horoscopes, creation myths and big bangs, regardless of their basis, are sites of human definition. The compelling story around our creation resounds with our ancestor worship. We are dwarves standing on the shoulders of giants and our achievements are solid because of the power of our foundations be they built by Yahweh or Newton.

In contemporary times space and space exploration captures the imagination because it has a pan-human character. The idea of space colonisation by corporations or countries is the cause of much horror and controversy, not least because space and celestial bodies still have strong romantic and cultural facet. The thought of a billboard in space or a horoscope where a person is born a Pfizer with a rising sign of Monsanto is at once comic but also reflects a grim probable reality. Perhaps the

SPACE HAS BEEN THE METAPHOR FOR SOCIETIES' OUTER CONSCIOUSNESS

greatest imaginative fuel of space is that it exists for the thinker as a collapse of Husserl's definition of space. It is at once a coalescence of human, cultural and geometric concepts of a physical other and a site that can be deconstructed and worked with. As much as we would like to define and understand it the totality of space remains unknown. As such it is a fertile canvas for artists.

Neither Batty nor O'Mally's work requires a photorealistic view of space (and we've avoided a technical critique of their work here in favour of investigating the concepts they describe); rather they must capture the potentiality of space, flatly described, to convey the psychological impact of it in order to facilitate the spatial way their art affects the viewer. Their depictions of space are thus intertwined with various tropes such as installation, the cosmic sense of space, space as a location, and the sense of proprioception, which is how we feel about our bodies as spatial objects, and the externalisation of that feeling as personal space. The paths of divergence for both artists lies in how they position the viewer with regard to their construction of space as a negating but sublime entity.

O'Malley's work on the other hand has a more landscape approach, and by extension his work might be considered an installation. Like a landscape painting we are shown layers of ground, a scene, and asked to consider ourselves in relation to the topographic vista. The viewer, drawn

into an existential game with the figure, becomes part of the play of objectification; at once the viewed and viewer, the reversed keyhole of the canvas is peered through to show the infinite. In good phenomenological fashion at the heart of the inner room is both self as an indivisible point (consciousness) and the universe.

The inner room is our own internal domain. We are infinite layers of shifting dependencies and contextual histories and values that slip away from full realisation

or control. In many early cultures the recognition of the fixed stars, returning phenomena and patterns of movement became the basis for astrological investigations. Artistically space being fixed but out of reach is an ideal template for considerations of what humans are and what it means to be in the universe. Both artists discussed here embrace the unanswerable nature of those questions within the negating concept of space: Batty by considering the multiplicity

of single perspectives and O'Malley by the infinity of perspectives with self and position in time and space. In both cases we are moved beyond the rational 'daytime' of definite position and concrete answers and into the imagination-rich 'night-time' of potentiality.

The way this functions for the viewer is not to answer the big questions but to make all little human questions irrelevant and in doing so liberate us from terrestrial, fixed positions and ideally allow us to consider other futures and fates.

O'Malley, D. (2019)

Interview conducted 28th Jan 2019, London with Kailas Elmer.

Trebuchet.

www.trebuchet-magazine.com